|

Who we are, where we've been, and where we're going.

Text by John Lawrence Reynolds. Copyrighted article, used with permission. This commemorative history was written for a publication of the Burlington Committee for the Ontario Bi-Centennial in 1984.

Somehow, we Canadians tend to believe that history is found only in schoolbooks, museums, or the occasional movie that stretches its plot to fit its actors instead of the other way around. In reality, of course, history is all around us every day of our lives.

It is in the names of the streets on which we live ... in the ways we earn our living ... and in the traditions we carry down from one generation to the next.

What's more, it is important for us to be familiar with history, especially within our own

community. History needn't be dead and dust-encrusted, like something in a glass display case. Instead, it is an ongoing story ... and so is the study of its effects and influences. By understanding where we have come from, we can begin to understand how we came to be who we are. And that's just as vital for communities as it is for individuals.

The year 1984 has been declared Ontario's Bicentennial Year, coinciding with the 200th-anniversary of the major influx into Upper Canada of British Empire Loyalists – those citizens of the U.S. who sought to escape persecution in the new republic as a result of their loyalty to the Crown.

It is also an opportunity for residents of Burlington to pause and consider the events of the last two centuries, and how they have shaped this city and this region.

Let's see where we came from. Let's understand how we got here. Let's consider where we're going.

Mention Burlington history, and local citizens immediately think first of one man: Chief Joseph Brant. It's easy to understand why. Brant, after all, was one of the most influential and charismatic men of his time, received at London as a king in his own right, recognized as leader of the powerful Six Nations peoples, and cultured far beyond the level of his average contemporary native or Anglo-Saxon.

But his residence here was brief, covering less than the last ten years of his life; the achievements that had made him famous, and for which he would be both loved and hated were all in his past by the time he settled at Brant House, located on the site of the hospital and museum that bear his name. Thus, our history as a community has been built perhaps too much around Brant as one of our first permanent residents, which he may have been; and as a kind of guiding spirit for the area, which he certainly never intended.

The fact is that Brant didn't receive a deed to property within what is now Burlington until 1798, as a reward for his services to the Crown. There is evidence that he had spent time on the Beach Strip, but Joseph Brant would likely be surprised to discover that Burlington claims him as a founding father; he clearly identified more with Brantford than with this area.

t's deed covered 3,724 acres, including lake frontage; it was there that Brant built his last home soon after he received the deed, and it was there that he died on November 24, 1807.

A man who inspired so many tales and myths in his lifetime was certain to generate them after his death.One of the local stories has it that Brant was buried in the cemetery at St. Luke's Church, and that his body was removed one evening years later to be carried to Brantford by torchlight on the backs of Six Nations tribesmen for reburial. It is a very romantic image, but unfortunately it is also all fiction; St. Luke's wasn't constructed for almost 30 years after Brant’s death, and it's unlikely that the body of the great chief would be interred deep in the forest alone. His grave was almost certainly chosen along the Grand River, on lands belonging to the entire Six Nations people.

Brant's daughter Elizabeth and her husband, William Johnson Kerr, were buried at St. Luke's however.

|

St. Luke's Church (Lakeshore view)

|

Elizabeth was apparently a charming and well-bred woman, while her husband served as a lawyer and politician, much in the mold of William Lyon Mackenzie. In a diary kept by Anna Brownie Jameson (published as Winter Studies & Summer Rambles), we can catch a glimpse of these two as

they appeared to a proper and impressionable Victorian Englishwoman when they emerged from a Hamilton-to-Toronto stagecoach in mid-winter: |

| . |

"The monstrous machine disgorged eight men-creatures, all enveloped in bear-skins and shaggy dreadnoughts, and pea jackets, and fur caps down upon their noses, looking like a procession of bears on their hind legs, tumbling out of a showman's caravan. They proved, however, when undisguised, to be gentlemen, most of them going up to Toronto to attend their duties in the House of Assembly.

"One of these, a personage of remarkable height and size, and a peculiar cast of features, was introduced to me as Mr. Kerr, the possessor of large estates in the neighbourhood, partly acquired, and partly inherited from his father-in-law, Brant, the famous chief of the Six Nations... Mrs. Kerr the eldest daughter of Brant, has been described to me as a very superior creature ... she looks and moves (like) a princess, graceful and unrestrained..."

|

Brant's legacy remains in a number of ways; John Street and Elizabeth Streets, in the city's original core area, were named for the two Brant children who remained here after his death.

Partly as a result of border skirmishes following the Revolutionary War, and partly because of Governor Simcoe's vision of London as the future capital of Ontario, British troops began construction a roadway to link York with Southwestern Ontario in 1793. It was kept well back from the lakeshore, not so much to prevent marauding attacks from American sailors and marines as to avoid the swamps and marshes which extended across much of the area between the escarpment and the water. The section between Burlington and York wasn't completed until well after Brant's death, and the route hasn't changed in almost 200 years. Nor, in fact, has the name. When first constructed it was called "Dundas Street," the name it is still known by in many communities, although it is officially designated as Highway # 5. (editors note: renamed again as Dundas Street in 2001)

The Burlington area escaped any major involvement in the War of 1812. Soon after the last battles were over, settlers began to take advantage of the peace and the availability of land in Nelson Township to enter the region and begin homesteading. This was largely a result of the Mississauga Purchase, which brought the last lakefront land held by the natives into Crown hands; thus, our area was among the most recent in Southern Ontario to be opened for agriculture and development.

Accepting the land, however, brought with it its duties and responsibilities. According to a Location Ticket dated December 1825, and awarding 100 acres of land in Nelson Township to a Robert Bates, the settler was to "clear and fence five acres for every 100 acres granted; build a dwelling house of 16 feet by 20; and clear one-half of the road in front of each lot" - all within two years.

Soon the individual pioneers, scattered here and there, and attracted merchants and mills, which, in turn, became the focal points of new communities.

The rise and eventual disappearance of these villages, many of them no more than footnotes in history books today, is one of the most fascinating aspects of Burlington's past.

One of the earliest settled areas was Aldershot, where Alex Brown, a Waterdown resident, relocated and built a wharf at LaSalle Park, named for the early French explorer who landed there before proceeding further into the North American interior. The site of Brown's Wharf eventually became known as Port Flamborough and, as we'll see, had an important effect on the agricultural and commercial development of the area.

The families who were attracted to the Aldershot area during the early years of settlement are familiar to us today in the names of streets such as Unsworth Avenue, King Road and Job's Lane. One influential family, the Filmans, arrived in the late Eighteenth Century, opening land along the bayshore from King Road to Indian Point. Avid bird-lovers, the Filmans are supposedly commemorated by "Birdland," the housing development with street names such as Finch, Lark, Tanager, Oriole and so on.

It would seem that these settlers brought some special qualities with them, because Aldershot has always had a fiercely independent quality about it, in spite of the fact that it was never incorporated as a village.

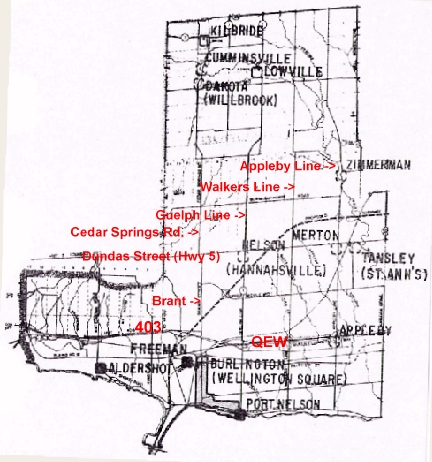

Other early communities were not so lucky. If you were asked to venture off to Cumminsville, Hannahsville, Tansley or Zimmerman, would you know where to find them? Probably not, because they haven't existed in many years. And only older generations could pinpoint the site of Port Nelson, Freeman, Dakota and Appleby today.

Yet each of these was a thriving village in its time, and their residents no doubt would be surprised to learn that the collection of shops and homes at the foot of Brant Street then called "Wellington Square" would one day become the focal point and namesake for the entire Nelson Township as the City of Burlington.

But it did, and the manner in which it grew, in fits and starts and eventually in a post-war explosion, is the basis of Burlington's story.

| Within the current boundaries of Burlington lie individual communities which grew during the Nineteenth Century. Many retain their identity today; other are merely footnotes to local history. |

|

Freeman

Located at the intersection of Brant Street and Middle Road. (now Plains Road)

|

Zimmerman

On Appleby Line, just above Burnhamthorpe. Named for Henry Zimmerman, who built the local mill. At one time, Zimmerman boasted three mills, a school, a shoe shop, tailor, blacksmith and post office.

|

|

Lowville

In the Twelve Mile Creek valley, where it crosses Guelph Line. (In early years, another settlement called "Highville" was begun on the hills above the town.) At its prime, Lowville counted a furniture factory, paint factory and agricultural equipment plant among its industries.

Dakota Mill

(and nearby Willbrook) – Just above Brittania Road, on Cedar Springs Road. More a site than an actual community. A water-powered grist mill still operated there until the mid-1970’s.

|

|

Cumminsville

About midway between Dakota Mill and Kilbride on Cedar Springs Road. In the 1850’s Cumminsville was the site of a post office, telegraph office, bakery, tavern, furniture manufacturer and several mills and blacksmith shops.

|

Kilbride

Established by William Panton about 1850 and named for a town in Scotland. In the late 1870’s the town reached a population of several hundred, with a number of commercial establishments. |

Hannahsville

Named for the wife of Caleb Hopkins, an early settler in the Guelph Line/No. 5 Highway Area. Around 1850, Hannahsville had three inns, a school and a church. Later, the community name was changed to Nelson and became the site of the original Nelson Township Hall.

Merton & Tansley (St. Ann’s) - Rural communities on Dundas Street (No. 5 Highway) between Appleby Line and Burloak. Originally called St. Ann’s, the easternmost settlement was renamed Tansley in the 1880’s, for the local postmaster to whom all mail was addressed. |

Appleby

Settled by the Van Normans, a prominent Late Loyalist family from Pennsylvania. Appleby was one of the earliest communities in the area and retained a strong identity well into the present century. Recent development at its site – the intersection of Appleby Line and the QEW – has obliterated almost every trace. |

|

One of the most vexing questions of Burlington's history is a very simple one: what is the source of its name? Was it, as some have suggested, an evolution of "Bridlington," the Yorkshire town? Or was its namesake the London suburb of the same name, long since absorbed within the English city?

Popular folklore leans towards the "Bridlington" origin - an idea supported by the revised City crest. But Governor Simcoe's wife refers to the area as "Burlington" in her diaries, and the name was well established by the time Brant settled here. Burlington Heights, where the High Level Bridge stands today, was a major area landmark at the time; what's more, the body of water known variously as "Macassa Lake" and "Lake Geneva" was officially designated Burlington Bay in 1792, long before any settlement occurred here.

There is, in fact, absolutely no direct reference to "Bridlington" anywhere in historical records. So, while we may never know the exact source of the name, it's safe to say that the area was referred to as "Burlington" from the very beginning.

When Brant's land began to be parceled off after his death, the settlers who formed the young community were seeking a clear identity for their area, distinct from "Burlington Heights" and "Burlington Bay." Naturally, their attention was at least partially directed back towards Britain, and everyone's attention there was on the hero day, the Duke of Wellington. Thus, Wellington Square. While legend has it that Joseph Brant named the hamlet in honour of The Iron Duke, the facts suggest that an early developer of Brant's land, Joseph Gage, was responsible. Wellington, after all, did not become a celebrity until the Battle of Waterloo, eight years after Brant's death. The other hero of the time, Lord Nelson, inspired names for communities in the area such as Palermo and Trafalger, as well as for the new Township of Nelson. In many ways, the history of Burlington is really the history of Nelson Township, and the story of the communities within its borders.

A Royal Act passed in 1792 established townships as the first imposition of government on this part of the country. Unfortunately, the survey was carried out by two individual surveyors working 11 years apart, leading to some interesting consequences.

The first was conducted by Samuel Wilmot in June 1808, who surveyed the area north from the lake as far as two concessions above the Dundas Highway. The balance of the Township had to wait until 1819 for surveyor Rueben Sherwood, who surveyed the lots in a different manner, running their lengths perpendicular to Wilmot's. Why change the direction? Only Sherwood knew, but the results can be seen to this day, where north-south roads above Highway #5 all contain a small "jog" at the 2nd Concession to account for the different surveying techniques.

In any case, the survey led to settlers clearing the land throughout the area, including much Brant's Block extending from west of Indian Point to Brant Street. Many of the settlers were Late Loyalists leaving the Revolution behind, and among them were the Ghents, wealthy plantation owners from North Carolina. Legend has it that many of our local apple trees were begun from seeds of Ghent trees in North Carolina. During a year spent in the Saltfleet area, the Ghents had started small trees from the seeds and supposedly carried the seedlings across Burlington Bay in canoes. The young trees, planted upon their arrival in Wellington Square, are said to have thrived in the sandy soil and launched an agricultural industry that was to sustain the are for more than 150 years.

English settlers formed the next small wave of newcomers to the western end of Lake Ontario. Those who had any energy remaining after a rough ocean voyage and the trek onward from Quebec or Montreal faced a difficult life in the unopened wilderness areas.

Throughout Nelson Township, communities were springing up at cross-roads and near mills and port facilities, while existing settlements expanded; Wellington Square grew from a cluster of 16 houses in 1817 to an impressive 400 inhabitants by 1845, when it could boast of a doctor, taverns, churches, and boat travel to Hamilton. During the early 1830's, Port Nelson welcomed the first rector of St. Luke's Anglican Church, Dr. Thomas Greene, as a resident. Natives of Ireland, Dr. Greene and his wife, like the Ghents, brought seedlings of their favourite plants with them - in this case, Mrs. Greene's prize roses. The Irish roses flourished in the sandy soil, inspiring the name that the area is known by to this day: Roseland.

In 1835, both villages were joined by the new Lakeshore Road (originally called "Water Street"), but it would be years before vehicle travel would surpass ships, especially for transporting cargo. Between the snow drifts of winter and the mud of spring rains, Upper Canada's roads were practically impassable six months of the year. In fact, few roads were to be found at all; the area was well behind much of what is now Southern Ontario in road building, as a result of its relatively late settlement. What's more, there were no navigable rivers in the area, so Lake Ontario became a lifeline to the region, bringing equipment and materials from abroad and carrying away exports to the rest of Canada and eventually to Europe. Many of the original roads in the region were built by settlers, whose contribution of labour was for a time accepted in lieu of taxes.

Unfortunately, there are no natural harbours between Port Nelson and Aldershot; to provide docking facilities, long wooden wharves were constructed, reaching like outstretched fingers into Lake Ontario. By the mid-1850's, the region boasted five commercial wharves - one at Port Nelson, three at Wellington Square, and Brown's Wharf at LaSalle Park, known by then as Port Flamborough. A steady stream of tall-masted schooners tied up and sailed away from all three locations at the height of the sailing seasons. During one hectic year, Port Nelson shipped more goods than Hamilton, a much bigger community.

And the cargo? Much of it was locally grown wheat and flour; in 1850, nearly 132 million bushels of wheat were grown in Upper Canada, the majority in the rich farmland of Nelson Township.

Wheat was traditionally the first crop into the soil when the land was cleared, and in the mid-1850’s a ready market was being generated in Britain. Timing was a critical factor; the Crimean War was raging, and Britain's colonies were being relied upon to provide raw materials to feed and equip the army. It should be remembered, as well, that Canada's developed land area ended, for practical terms, at Windsor; thus Southern Ontario, and not Saskatchewan, was the "bread basket" of Canada, and Burlington-area docks provided the shipping facilities. |

Wharfs at Wellington Square

|

| At the height of the harvest seasons, farmers from many miles north and west of the Lakeshore would set out in wagons loaded with grain, often waiting in lines reaching from the wharves at the foot of Brant Street all the way back to Freeman. |

In the latter half of the Nineteenth Century, changes occurred which altered the emphasis on wheat in Nelson Township. The export markets died off, a gradual move towards western wheat began, and our local farmers followed the normal evolution of land use, moving from wheat to mixed crops.

At one point, Nelson Township apples were being shipped to England and South Africa from Brown's Wharf. Melons, too, became something of an area specialty, particularly those grown in Aldershot soil; for a period of time, an "Aldershot melon" was almost as common a term as a "P.E.I. potato" or a "B.C. apple" is today.

Parallel with the strong grain industry, lumbering became an important part of Wellington Square's commercial life in the mid-1800's. Cutting down trees not only provided much-needed timber to construct homes and ships, but also opened the land for agriculture and homes.

|

|

| Saw & Planing Mills of W.J. Douglas, Port Nelson |

Alex Duffes' Store & Storehouse, Burlington |

Naturally, the settlers who toppled trees weren't interested in replacing them with similar stands of young oaks, elms and beech. And just as naturally, the lumber boom was relatively short-lived.

Still, it was prosperous while it lasted. By the mid-1800's, Nelson Township could boast of 17 saw mills, all water-powered and all generating hamlets around them, such as Kilbride, Lowville and Zimmerman. Most of the timber was marked for export, and when grain carts weren't lined up along Guelph Line and Brant Street waiting for the ships, lumber carts were. Lower-grade wood was cut and sold as fuel for the many steamers plying up and down the Great Lakes, their high stacks trailing plumes of thick black smoke and cinders.

Timber destined for local use required yards and dealers, and there were several large lumberyards in Wellington Square and Port Nelson at the time. Customers who came into the villages for lumber looked for other supplies as well, and from 1860 to 1880 Wellington Square was humming with activity.

Many homes in the original Brant's Block area have been beautifully maintained and give some idea of the lifestyle Burlington residents enjoyed in the late Nineteenth Century.

Excellent brochures have been prepared by the Local Architectural Conservation Advisory Committee of Burlington (LACAC), to be used as guides for walking and driving tours of Burlington; they may be obtained at the Clerk's Office, City Hall; and the Tourist Information Centre on Lakeshore Road. In the meantime, here are just a few of the highlights you can discover on your own.

|

|

| 468 Locust Street. Built in 1884 in the Gothic Revival style. Features fine handcrafted carpentry on the gables and verandah. |

| 1375 Ontario Street.Burlington's famous "Gingerbread House", constructed in 1893 by Burlington's prominent builder A. B. Coleman, who also built Fort Erie Race Track, U. of T. Convocation Hall, and three buildings at the C.N.E. Count the number of different windows in this house (one is in a chimney!). |

| 479 Nelson Street.Dates from 1873, in the Second Empire style with mansard roof. The coach house in the rear had quarters for the stable boy. |

| St. Luke's Church (Ontario Street). Originally built in 1834, but with many changes made over the years. Look for the graves of Joseph Brant's daughter and her husband, William Johnson Kerr. |

| Knox Presbyterian Church(Elizabeth & James Street). Andrew Gage and his wife donated the land in 1845; the current structure dates from 1877 and features 12 stained-glass windows manufactured in Britain and donated by John Waldie, a prominent local businessman of the time. |

|

All of this commercial development provided jobs.

Jobs attracted workers. And workers needed homes in which to live and raise their families.

While the earliest settlers had begun farming in the Indian Point area, the heart of Wellington Square was on land originally awarded to Joseph Brant. But for the first forty years, there was little to indicate that Wellington Square had a future any more promising than other hamlets in this part of Upper Canada. Significant advances during this period were few and far between: the completion of the canal through Burlington Beach into the Bay and the launching of regular stagecoach service to Hamilton and Toronto are about the only highlights.

It was the burgeoning grain and lumber trade that blossomed in the 1840's and matured for the next thirty years that made Wellington Square something of a focal point. Grain and lumber handling, ship-building and maintenance, and other trades attracted workers to the Lakeshore area stretching from Port Nelson to the Aldershot shoreline.

Their arrival generated other services and the people to provide them - physicians, foundries, taverns, bakeries, wagonmakers, tinsmiths, grocers, dry goods merchants, and on and on. With all of these services, plus the convenience of transportation via steamer, stage and rail (the railroad arrived in 1854) and the cooling winds off the Lake in the summer, |

Store of John Waldie & Co., Burlington

|

| Wellington Square became an attractive community in which to settle. Or so the 800-odd residents believed when they petitioned to have Wellington Square incorporated as a village in 1873, with its name changed to Burlington.

|

Growing up during the first years of Burlington as an incorporated village seems like some northern Huck Finn story to us from the viewpoint of the late Twentieth Century. The village extended from the Lakeshore on the south to the apple orchards north of Caroline Street. At the foot of Brant Street, high-masted schooners sailed in from faraway destinations such as Kingston, Montreal and Windsor. In the summer sun, boys would sit on the wharves and watch the stevedores at work, while the sound of hammers on hot steel rang from the blacksmith shops and the rattling wheels of the afternoon coach from Hamilton echoed along the road.

|

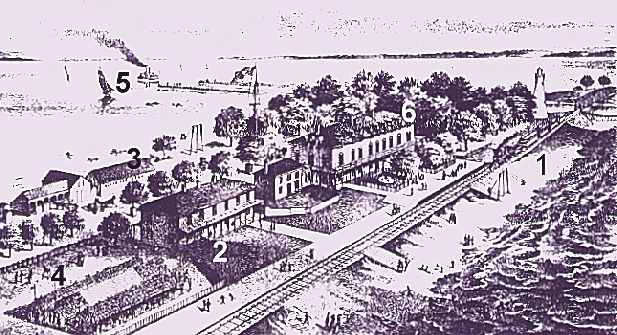

OCEAN HOUSE, The "Long Branch" of Canada.Situated on Burlington Beach between Burlington

Bay and Lake Ontario. Access to Hamilton by

Rail (1) and boat (5) hourly.

"The coolest resort on the Continent!"

(2) Music Hall, Bowling & Billiards.

(3)-Boats for Hire. (4) Lawn Bowling. (6) Ocean House |

|

| . |

In good weather, excursions lasting a full day might be made to visit the strawberry and melon fields of Aldershot, or the water-powered mills at Dakota, Lowville or Kilbride. Sundays meant church or Sunday School at St. Luke's for the Anglicans, St. John's for the Catholics, Knox Church for the Presbyterians, Calvary Church on Locust Street for the Baptists, or perhaps the Methodist Church on Elizabeth Street, which eventually became headquarters for the Burlington Sea Cadet Corps. (Churches in the northern portion were predominantly Methodist; East Plains, Kilbride, Lowville and Zimmerman all had Methodist churches, many of them still active today, although often for other denominations. Bethel Chapel on Cedar Springs Road was a Methodist church as well. Only Lowville, of all the communities above Dundas Street, had a strong Anglican congregation outside of Burlington.)

During the school term, classes would be attended at Central School on the same site as the building bearing its name today. But it would be long after the turn of the century before students could proceed beyond the eighth grade without, commuting into Hamilton each day. |

The original Brant Home was standing in 1875 when it was incorporated into a summer resort known as Brant House. Here, amid twenty acres of gardens, croquet lawns, ice cream parlours and dance halls, Brant House attracted tourists who relished the view out over Lake Ontario and the cool breezes that wafted off the water.

|

The Brant House. A beautiful Summer Resort & European Hotel situated on one of the choicest sites overlooking Burlington Bay & Lake Ontario.(Halton Illustrated Historical Atlas)

It was a busy place with row boats and a larger vessel (1) in Burlington Bay. The train in the foreground (2) on the Beach Strip is heading for Niagara Falls while the train barely visible at the top (3) just left the Freeman Station at Brant and Plains Road on its way to Hamilton. |

|

Eventually the Hotel Brant was built adjacent to the Brant House and became one of the outstanding attractions of its time, with elevators, electric lights, fancy dining and expensive room rates starting at an impressive $2.50 per day and up. Brant House became a veteran's hospital after World War One and was torn down during the 1930's - but not before it had spawned the Brant Inn, which launched an era of its own into the 1960's. Many of the structures built in the latter part of the 1800's served a totally practical purpose as commercial and industrial establishments, although the area was never known as an industrial centre. Still, grain warehouses, a carriage factory and a wire works were prospering at the time of the village's incorporation in 1873.

Further afield at Dakota Mill on Cedar Springs Road, a more ominous industry was also busy. The Canada Powder Company was established there in 1854 as part of the youthful Dupont Chemical Company, using heavy equipment dragged from Burlington Beach to Wellington Square and up the escarpment behind thirteen yoke of oxen. By 1884, the firm had changed hands to the Hamilton Powder Company, producing gunpowder and blasting powder among widely separated buildings in the valley of Twelve Mile Creek.

The powder company employed 200 men, most of them from the villages of Kilbride and Cumminsville. It was an impressive operation, blending sulphur from Turkey, saltpetre from Chile, and charcoal from its own kilns, using local willow wood. Some of its production went to the CPR, blasting its way to the Pacific coast; a few historians speculate that Canadian gunpowder from Nelson Township was exported to the U.S. for use in the American Civil War. In any case, the demand for black powder was strong enough to keep the plant on a 24-hour production schedule for many years.

It all ended, however, on October 8, 1884. Most of the employees had left for their lunchbreak and to this day no one knows exactly what happened. Whatever triggered the event, the resulting explosion was heard as far away as St. Catharines, and the black mushroom cloud that rose above the ruins could be seen from Hamilton. Miraculously, only four were killed in the blast, but the disaster destroyed the industry, the livelihood of hundreds, and in many ways the future growth of the surrounding villages.

What's more, the silence that followed the Dakota explosion lasted for several decades and the region became somewhat sleepy and by-passed for many years.

The explosion at the Dakota gunpowder factory was not responsible for the decline in the growth of Burlington and the rest of Nelson Township, but it does make a dramatic punctuation point. The actual causes for the slowdown in expansion were the depletion of the forests, ending the lumbering boom; and the shift of local agricultural products from export markets for grain to local markets for fresh produce. In addition, the construction of railroads and the development of larger, steam-powered ships meant that Burlington, Port Nelson and Aldershot wharves were by-passed in favour of bigger facilities at Hamilton and Oakville.

All of this produced a change in the Burlington area between the 1890's and World War One - a change from grain and lumber for export to fruits, vegetables, dairy and meat products for local consumption.

Burlington's orchards had been successful since the days of the Ghent family and their Saltfleet-born seedlings. With the change in agriculture to fresh produce, local farmers began relying on fruit production as a major income source, and larger orchards were developed, especially along No. 5 Highway. Other large stands of apple trees could be found along the Oakville-Burlington Town Line, in the Strathcona area between Walker's Line and Appleby Line, and on the site of the present Burlington Mall, where the Fisher family had maintained orchards since the 1830’s.

The move from grains to fruits and vegetables had an interesting effect on land values. In the early years of Burlington's growth, the area around Maple Avenue could barely be given away because its sandy soil wasn't suitable for grain. But the loose, well-drained soil was recognized as perfect for market gardening in the 1880's and for almost a hundred years, until its sacrifice to development and more recently, to the second Skyway Bridge highway approach, it was one of the region's top vegetable producers.

To exchange information and improve their productivity, farmers formed the Burlington Horticultural Society in 1889, an organization that was as much a hard-nosed business cartel as it was a fraternal collection of growers. Members of the Society not only experimented with hundreds of plant varieties and various growing techniques, but also entered their produce in competition around the world. By the turn of the century, Burlington fruits and vegetables were winning honours at exhibitions in Glasgow, Paris and Chicago, and Burlington had acquired the title of "The Garden of Canada."

It was more than a garden, of course; it was Burlington's major industry at the time. And like all successful industries, market gardening spawned others. Around 1900 the Burlington Canning Company, later called Canadian Canners, was constructed at the foot of Brant Street expressly to pack local produce. For decades afterwards, the lower Brant Street area functioned with the scent of tomato ketchup in everyone's nostrils almost every working day. (A sample of the product can be seen at the Joseph Brant Museum, in its original can; the Burlington Canners brand eventually became absorbed into the Aylmer brand, part of the Del Monte organization.)

Another canning firm, Tip Top Canners, operated for many years in Freeman near the Plains Road and Brant Street intersection. And the Glover Basket Works was a successful company from the 1890's to the mid 1960's, with its large premises facing Brant Street near the railroad crossing.

Unfortunately, we have nothing but momentoes and memories to remind us of this period today; both Tip Top Canners and the basket factory burned in spectacular fires in the mid-Sixties, and the Canadian Canners plant was razed for development during the same period.

Burlington dozed through the late-Victorian period, adding its first local newspaper in 1898 (the Burlington Gazette), and its first library building in 1906. The electric Radial Line was declared another giant step in Burlington's development when it arrived about 1900. The Radial Line was a marvel of its day, providing convenience and relatively comfortable travel between Burlington and Hamilton to the west and Oakville to the east. Within Burlington itself, the line ran across the Beach Strip, up Maple Avenue to Elgin Street, finally stopping at the town station, now a public parking lot on Brant Street. The Oakville leg set off through Lion's Club Park and along New Street, where until recently the crumbling foundations for the line's bridges could still be seen at various locations. Radial Line service ended in 1929, replaced by more efficient, but less colourful, buses.

With the outbreak of war in 1914, 300 Burlington men volunteered for service and trained in a shed at the comer of Lakeshore Road and Locust Streets before marching up Brant Street behind a lone piper and boarding the train at Freeman Station. The names of the 38 who didn't return, along with another 44 Burlington men who made the same sacrifice in World War Two, can be found on the cenotaph alongside the Burlington City Hall on Brant Street.

Between the Wars, Burlington began to grow as a prime residential area, a hint of the explosion that was to begin in the 1950's and extend for the next two decades. Roseland, east of Guelph Line, became the site of impressive homes, and paved roads encouraged the use of automobiles, which, of course, changed things forever.

Industrial growth was generally small. Niagara Brand Chemicals, founded by "Mac" Smith, Burlington's first mayor, and Vera Chemical Co. (later to become Hercules Powder Ltd.), generated some employment with their growth, while Aldershot's unusual soil spawned gravel, brick and clay sewer pipe operations. But a true industrial base wasn't created in Burlington until the late 1950's,when an Industrial and Development Committee was formed to encourage industry to locate here.

The result was a remarkable success for a number of reasons. The completion of the Queen Elizabeth Way in 1939, and its route around the northern and western fringes of the town at that time, gave Burlington an advantage in transportation, especially in view of its location between Toronto and the U.S. border. Railway lines added to the transportation aspect of its appeal, and relatively cheap electrical power from Niagara completed the picture. In the midst of it all came the "escape to the suburbs" movement of the 1950's, when families were seeking to leave the noise and dirt of cities behind in favour of open lots and ranch-style homes; Burlington filled the bill perfectly.

(An interesting sidelight concerns the location of Ford of Canada's giant manufacturing facility in Oakville during the early 1950's. Oakville Town Council passed by-laws discouraging suburban development, and the Ford workers were thus attracted to Burlington, where their search for homes spawned the creation of surveys such as Mountain Gardens, Elizabeth Gardens and White Pines.)

As an extra incentive, the town purchased unused land north of the Queen Elizabeth Way from Studebaker of Canada in 1958 and created Progress Park as a light industrial development. The immediate and long-term success of this concept can be seen today by driving along Mainway Avenue.

The success of Burlington's move from agriculture to light industry was mixed, like so many of life's blessings are. Orchards and farmland within the corporate limits (which became Canada's largest town in 1958 with the amalgamation of Burlington Aldershot and the balance of Nelson Township) were suddenly transformed into some of the most valuable residential land in the Province. The completion of the Burlington Skyway Bridge in 1958 brought the town a half-hour closer to Hamilton, increasing its appeal as a suburban community. And the influence of the automobile continued, again with mixed results: Brant Street, once shaded by tall hardwood trees that formed a green arbour above the summer traffic, was modernized and widened; by the mid-1960's the trees were gone and, with the creation of the Burlington Mall on the site of Fisher's Farms, so was the undisputed role of Brant Street as the commercial centre.

On January 1st, 1974, Canada's largest town became Canada's newest city, with a population of 100,000. Older residents may reminisce about the loss of landmarks like the Brant Inn, where name entertainers such as Johnny Mathis, Andy Williams, Count Basie and others appeared on a regular basis, and about prime agricultural land that now sprouts swimming pools and car-ports instead of orchards and vegetable crops. But then again, we also enjoy fine recreational facilities, open parks, superb libraries; and all of the modern amenities we have learned to take for granted. Remember, too, that the climate, the escarpment, and the cool summer breezes from the Lake haven't changed since the arrival of the Loyalists; they hold the same appeal today as they did 200 years ago.

| TO LEARN MORE ABOUT YOUR CITY |

| visit the Joseph Brant Museum, or obtain walking and driving tour guides from the City Clerk's office at City Hall and the Tourist Information Centre on Locust Street, just off Lakeshore Road. A number of excellent historical and reference books on Burlington exist; many of them are at the Central Library on New Street, and at the Mary Fraser Library on the second floor of the Brant Museum. If you wish to take a more active role in the compiling of local history, visit Information Burlington at the Central Library on New Street and enquire about meetings of the Burlington Historical Society. It's your city. Discover it, and you'll discover something about yourself. |

|

|